In 2012, the conservation group Americans Rivers ranked the Potomac one of the nation’s most endangered rivers. As 2013 came to a close, the Potomac Conservancy issued a more comprehensive report card with its latest take on the Potomac’s status. Considering five major indicators – fish, habitat, pollution, land and people – the Conservancy awarded the Potomac a mediocre “C” overall. In other words, things are getting better, but there’s still a long way to go.

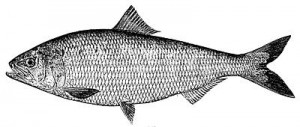

Some indicators scored well. The Potomac watershed maintains 25% of its land in protected status, surpassing the 20% goal set for the Chesapeake Bay region as a whole by the Chesapeake Bay Program. American shad have made a tremendous comeback, exceeding population goals set by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (based on 1950s levels) and making the Potomac one of the best locations for shad on the East Coast. In addition, thanks to the Clean Water Act, most wastewater treatment facilities now have limits that meet water quality standards, reducing pollution loads from a major source historically. Those reductions have helped drive nitrogen levels down, earning the Potomac a respectable “B” for nitrogen load.

But a closer look beneath the surface reveals remaining trouble spots. After all, the Conservancy’s “C” grade translates to a score of only 40-59% out of 100. When I went to school, anything under 65% was considered an “F.”

Phosphorus levels, largely from agricultural sources, remain high, earning a “D” from the Potomac Conservancy. Forested buffers along agricultural lands scored only slightly better, based on figures from USDA’s Conservation Reserve Program. As we reported last week, forested buffers are particularly important for achieving water quality goals. The Chesapeake Bay Foundation estimates that at current rates of conversion, the Bay watershed as a whole won’t meet its forested buffer goals for restoring the Bay by 2025. Stream water quality levels overall scored a “D” based on the Chesapeake Bay Benthic Monitoring Program’s health index. And underwater grasses, which need clean clear water to thrive, also scored poorly, reaching only 32% of the threshold levels set by a University of Maryland Center for Environmental Sciences assessment.

No doubt the Potomac is much healthier than it was in 1965 when sewage flowed freely and President Lyndon Johnson called it a national disgrace. But when the Potomac Conservancy looks into its crystal ball, it worries about future development undoing these gains. Housing, construction, impervious surfaces (such as roads and parking lots) and population all will grow in coming decades. And although shad are returning and striped bass (rockfish) are at sustainable levels, fish in the Potomac face new threats, including endocrine disruptors that mimic hormones and heavy metals that contaminate their tissues. For the Potomac to continue improving, communities, businesses and individuals will have to tackle new sources of pollution.

Fortunately, there are ways to do this. Check out some of the resources and opportunities offered by the Potomac Conservancy, Piedmont Environmental Council, Chesapeake Bay Foundation, Goose Creek Association, Whitescarver Natural Resources Management LLC, Natural Resource Conservation Service’s Gaining Ground project and other Downstream Project partners, and help make a difference.