Tucked away in a tiny notice in the sports digest of The Washington Post this week was one line that spoke volumes. The notice was reporting on the results of the ninth Annual Events DC Nation’s Triathlon benefiting the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. The line read: “…the swimming portion of the event was canceled due to a significant sewage spill in the Potomac River resulting from Saturday night storms.”

Anyone who’s watched the Ironman Triathlon on television and agonized with participants who’ve trained for months or years to take on one of the biggest physical challenges of their lives knows that triathlons have three parts: running, biking and swimming. (That’s where the “tri” comes from). If the water is so dirty that no one can swim in it, that’s not a triathlon. (It’s not really a biathlon either, since that seems to be the name for a winter sport involving cross-country skiing and target shooting that most of us only hear about every four years during the Winter Olympics.)

Somehow, the nation has gone from the Clean Water Act goals of all U.S. waters being “swimmable” and “fishable” by 1985, to quietly acknowledging that major public events like the Nation’s Triathlon can be truncated by unswimmable waters (in the nation’s capital no less).

How can that be? The technical reason is something called combined sewer overflow (or CSO in water quality jargon). Some older municipal water systems combine pipes carrying human waste from buildings and industrial waste from businesses with stormwater runoff that enters drains with rainfall or snow. About 722 municipal systems across the country rely on combined systems for some or all of their wastewater. Normally, these pipes send all this waste to a wastewater treatment plant for cleanup (although even in top form, these plants aren’t designed to remove all the substances entering our waterways today).

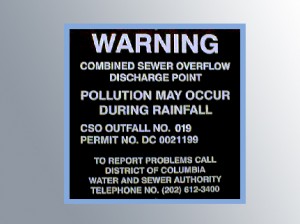

But heavy rainfall – like last weekend’s downpour – often overwhelms combined sewer systems and treatment plants. The excess water that the system can’t handle gets dumped directly into streams and rivers. That means everybody downstream gets a flashback to 1972 – the year the Clean Water Act was passed – and the raw sewage that was common in waterways back then. In Washington DC, where about a third of the city’s sewer systems are combined, this kind of thing isn’t unusual – the city’s Water and Sewer Authority posts signs at the city’s 53 combined sewer outfalls warning people of unhealthy water after rainfall events. Each year, 1.5 billion gallons of diluted sewage runs into the Anacostia River alone. Outfalls on the Potomac and Rock Creek add even more.

But heavy rainfall – like last weekend’s downpour – often overwhelms combined sewer systems and treatment plants. The excess water that the system can’t handle gets dumped directly into streams and rivers. That means everybody downstream gets a flashback to 1972 – the year the Clean Water Act was passed – and the raw sewage that was common in waterways back then. In Washington DC, where about a third of the city’s sewer systems are combined, this kind of thing isn’t unusual – the city’s Water and Sewer Authority posts signs at the city’s 53 combined sewer outfalls warning people of unhealthy water after rainfall events. Each year, 1.5 billion gallons of diluted sewage runs into the Anacostia River alone. Outfalls on the Potomac and Rock Creek add even more.

Thankfully, under pressure from the EPA, the city is undertaking a massive long term project to store the excess flow in underground tunnels during rainfall events. Then, the stored water can be released more slowly after storms and get processed through the Blue Plains Treatment plant before heading downstream. The city currently is proposing to revise the plan to replace some of the planned tunnel space with green infrastructure that can help reduce stormwater runoff rushing into sewer drains.

Kudos to EPA and DC for finally taking this problem seriously (and to DC Water and Sewer Authority for such a entertaining – yes really – video explaining the project). It’s one more big piece in the regional water quality puzzle in which cities, farmers, homeowners and developers need to each do their part to clean up our waterways. Perhaps by 2025 when the $2.6 billion project is scheduled for completion, triathlons will no longer be confused with biathlons and we’ll finally meet the Clean Water Act’s 1985 goals.

Well, better late than never.